New Delhi/Gandhinagar, India, May 23, 2023

Millions of low-income households and micro and small enterprises (MSEs), especially women-owned MSEs, will have improved access to finance, with investment from IFC and M&G Catalyst in India’s first securitization fund aiming to strengthen the securitization market and address gender gaps in formal finance, while expanding additional financing for MSEs in the country.

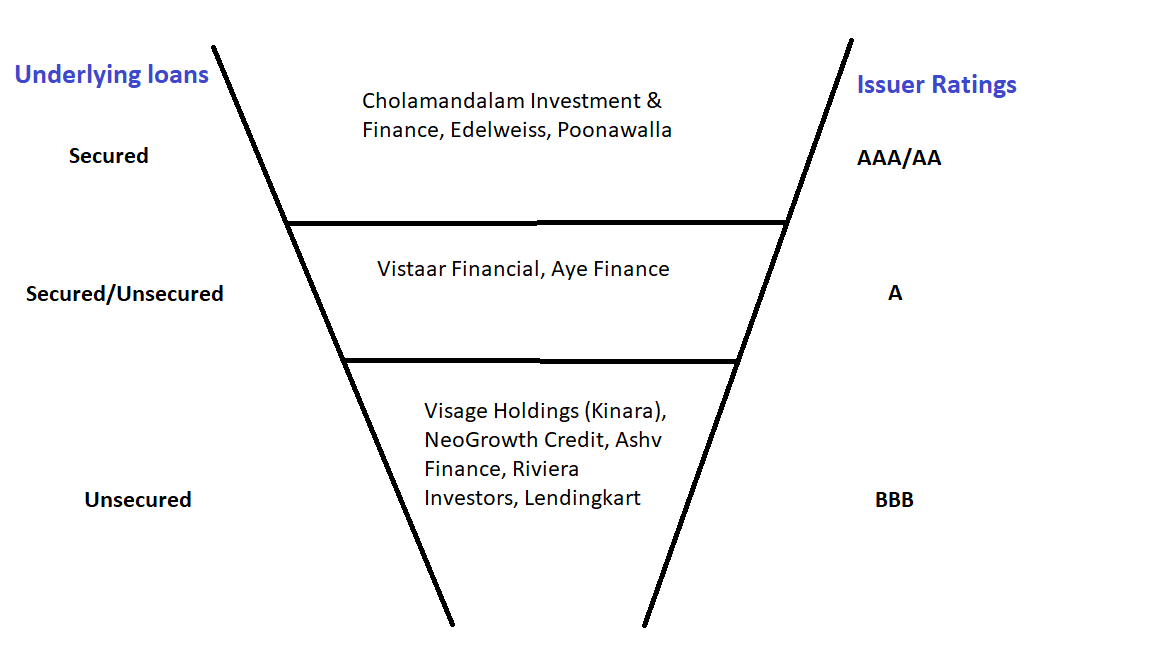

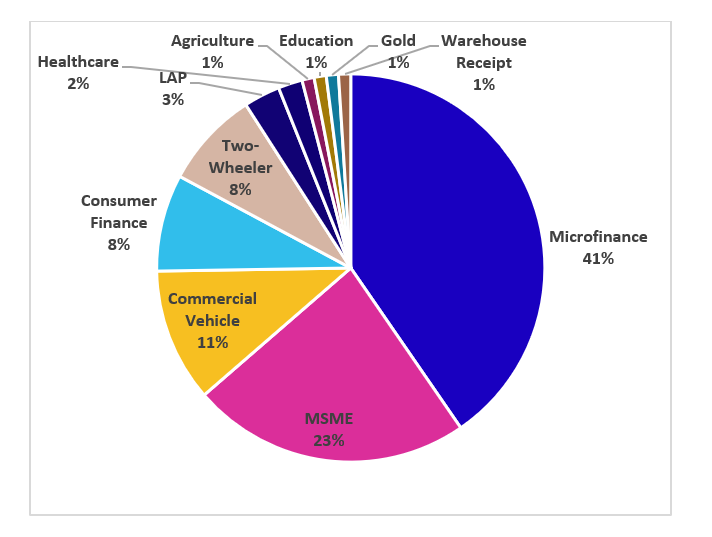

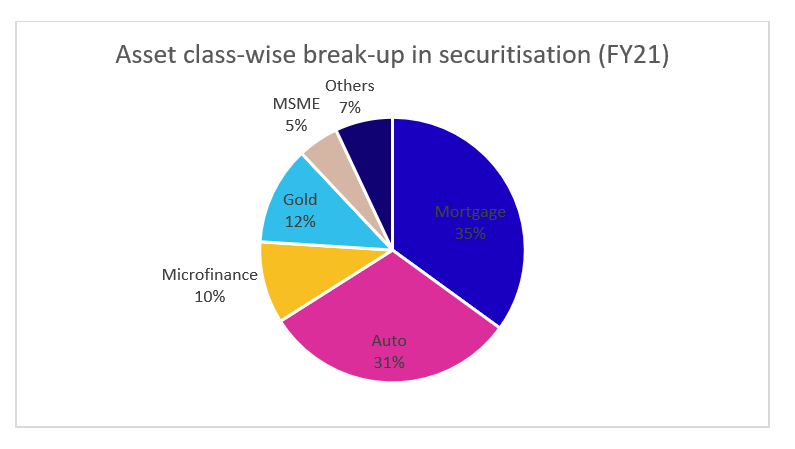

Vivriti India Retail Assets Fund (VIRAF) will be a first-of-a-kind asset-backed securitization (ABS) fund in India. IFC has invested US$30 million in VIRAF, managed by Vivriti Asset Management and backed by a capital commitment of $75 million from M&G Catalyst—a global private assets strategy within leading international investment manager M&G Investments. The fund will focus on scaling investment in securitized debt securities with MSE-backed assets—predominantly microloans to MSEs, which will constitute about 90 percent of the portfolio.

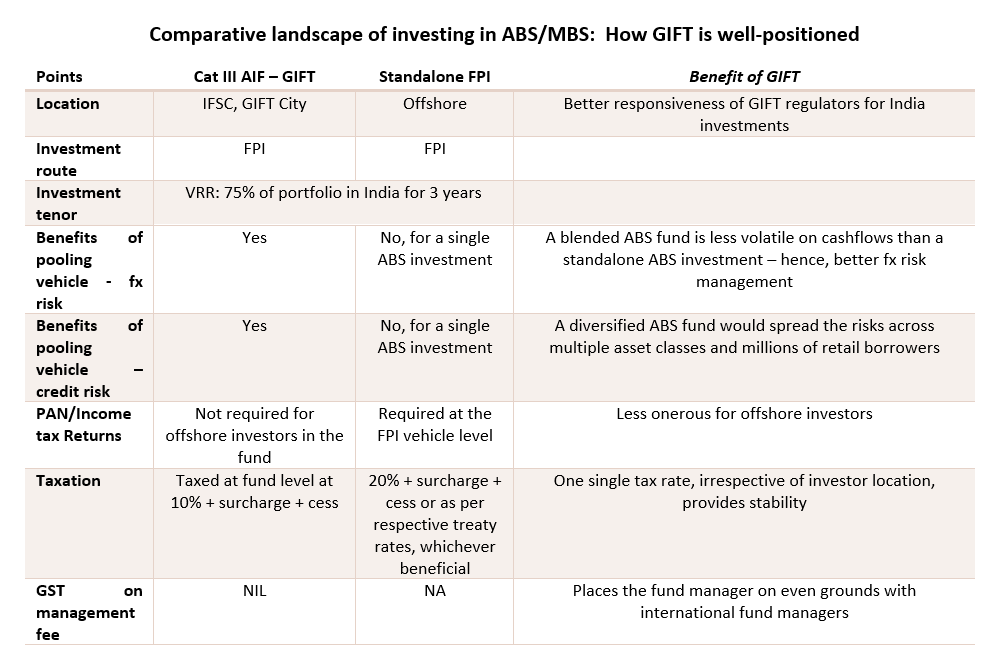

VIRAF has a fund term of 10 years with a target Assets under Management of $250 million and is domiciled in GIFT City, International Financial Services Centre. IFC’s and M&G Catalyst’s participation is also expected to attract other investors, mobilizing funds to channel to non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) that focus on supporting underserved MSEs in India.

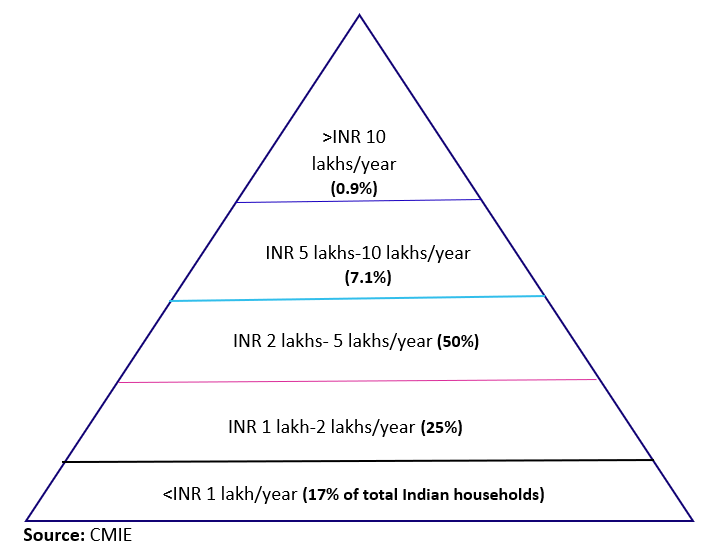

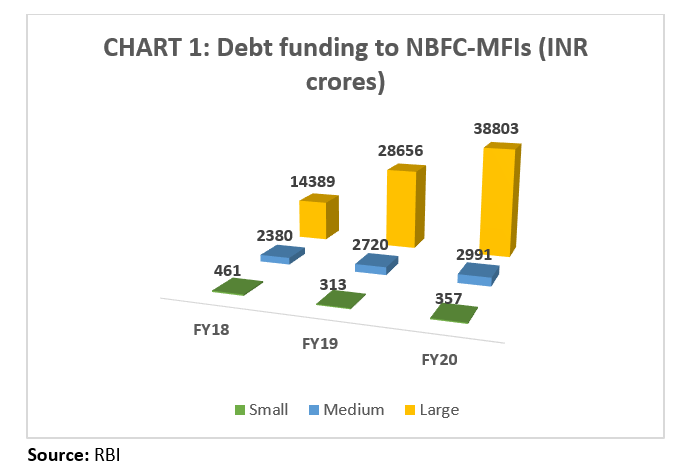

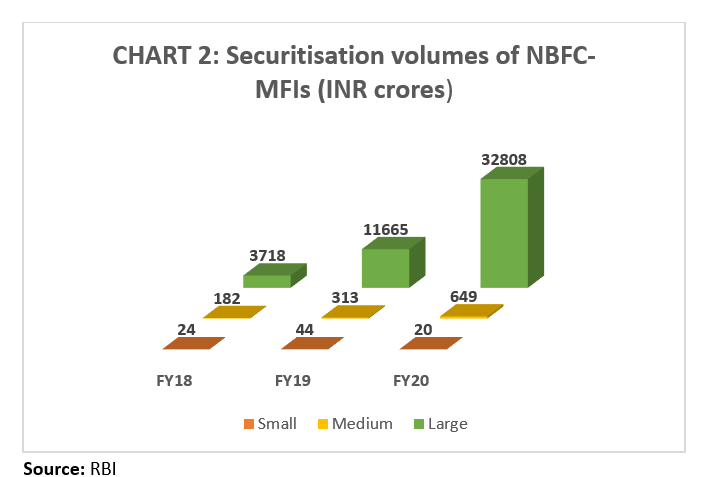

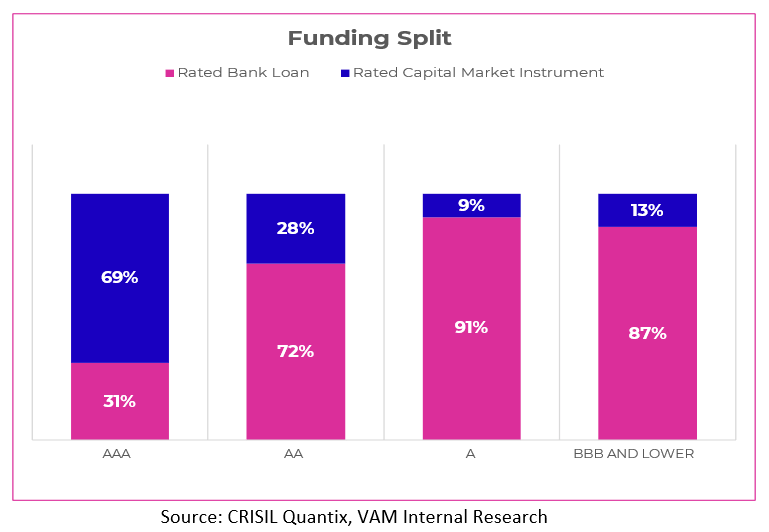

India’s 63 million micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) contribute up to 30 percent of GDP, generating over 40 percent of exports, and creating employment for over 100 million people. Yet, IFC study estimates the MSME finance gap in India is $342 billion, with MSEs accounting for 95 percent of that gap. IFC’s investment will help financial institutions offload existing MSME loans while unlocking capital to support MSME growth.

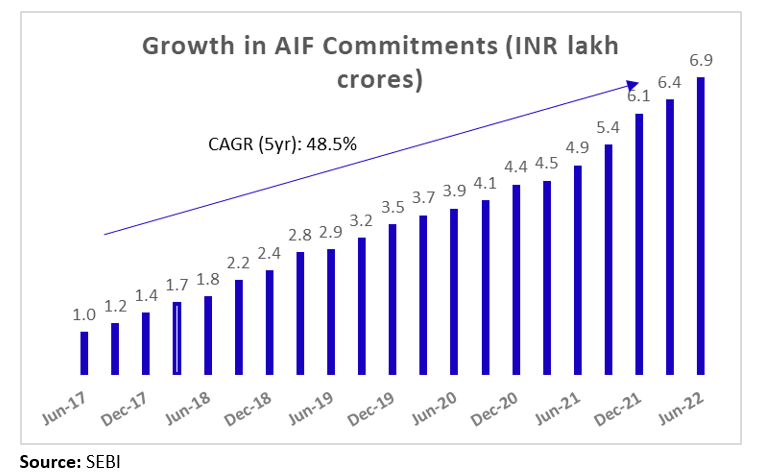

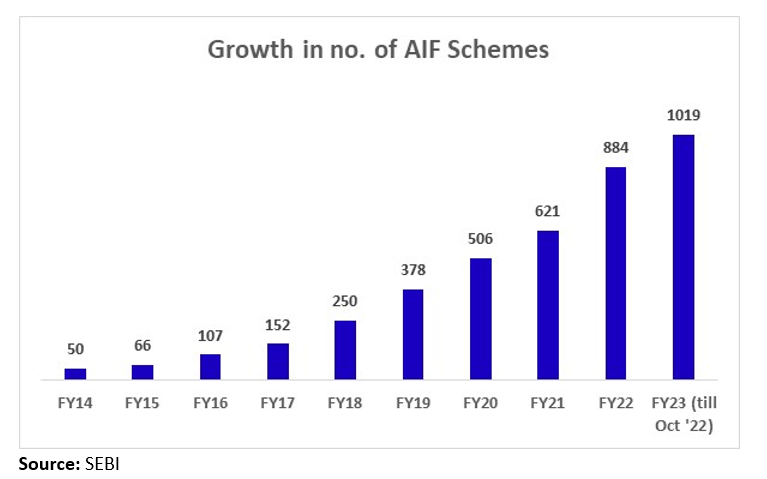

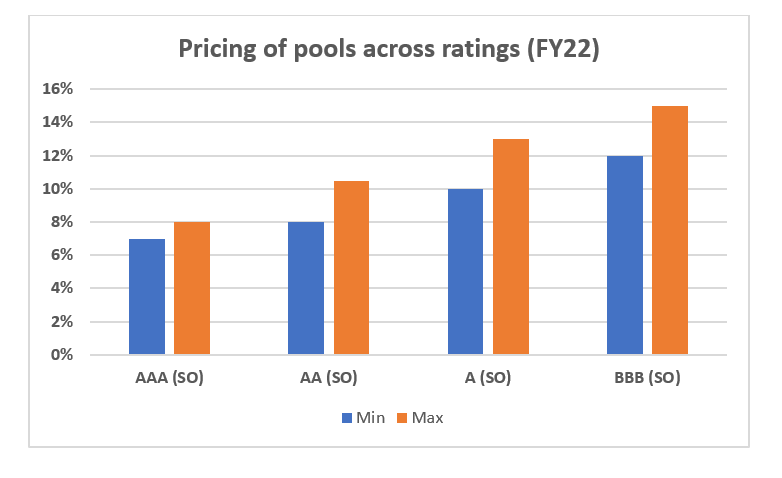

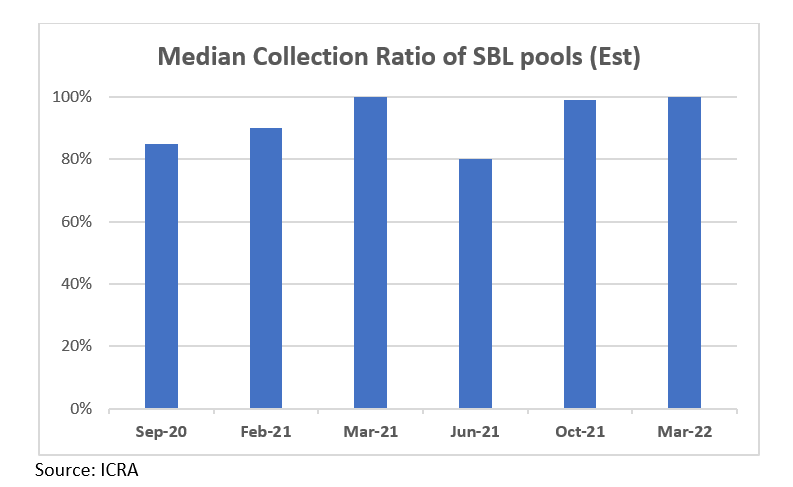

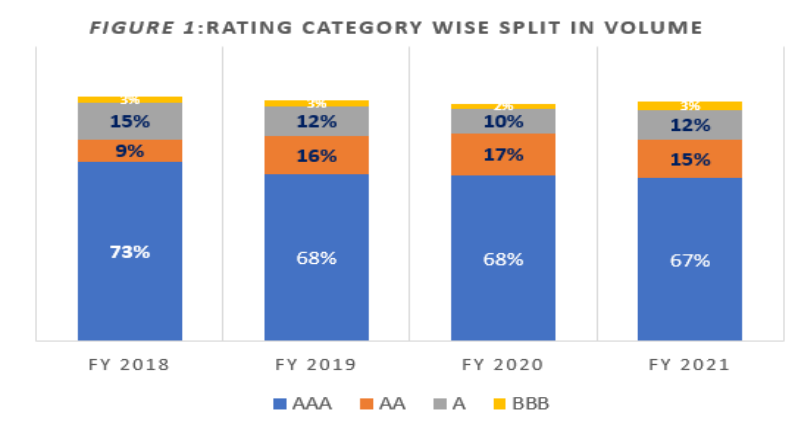

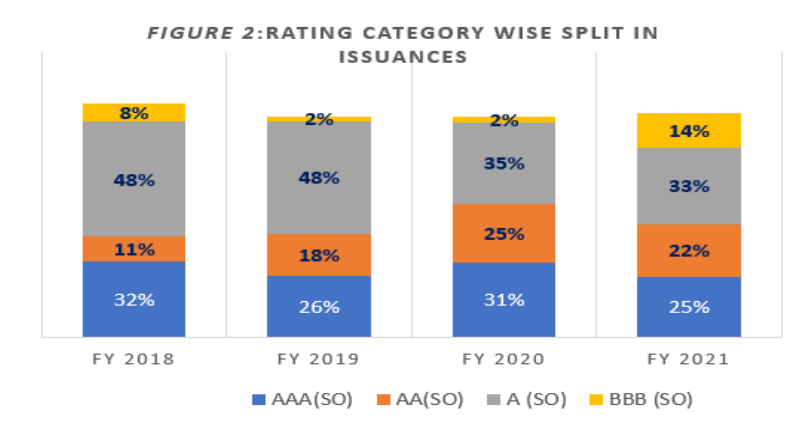

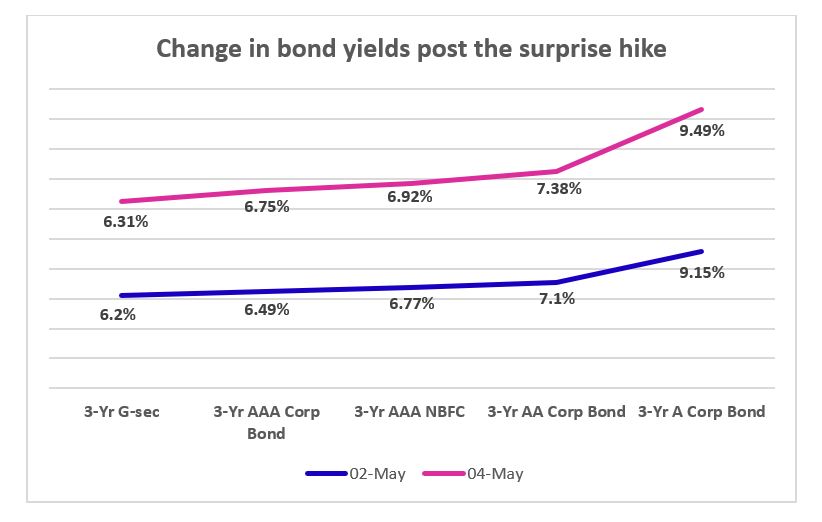

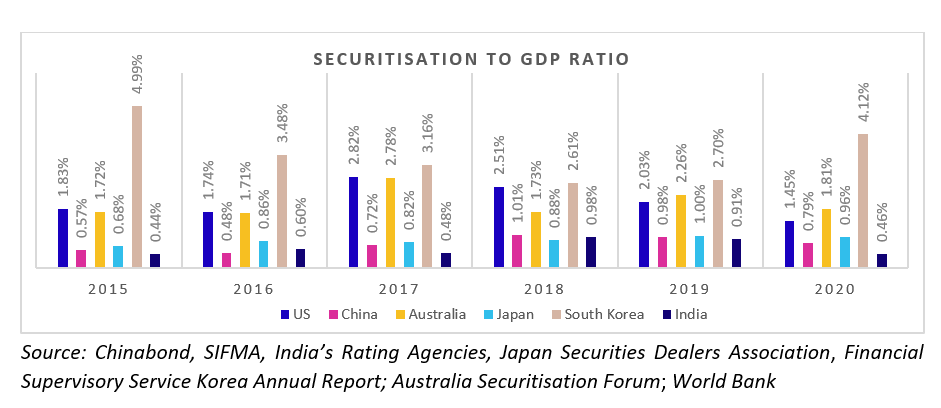

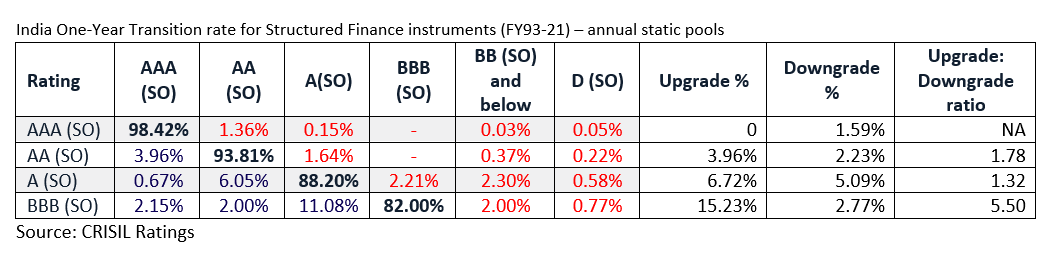

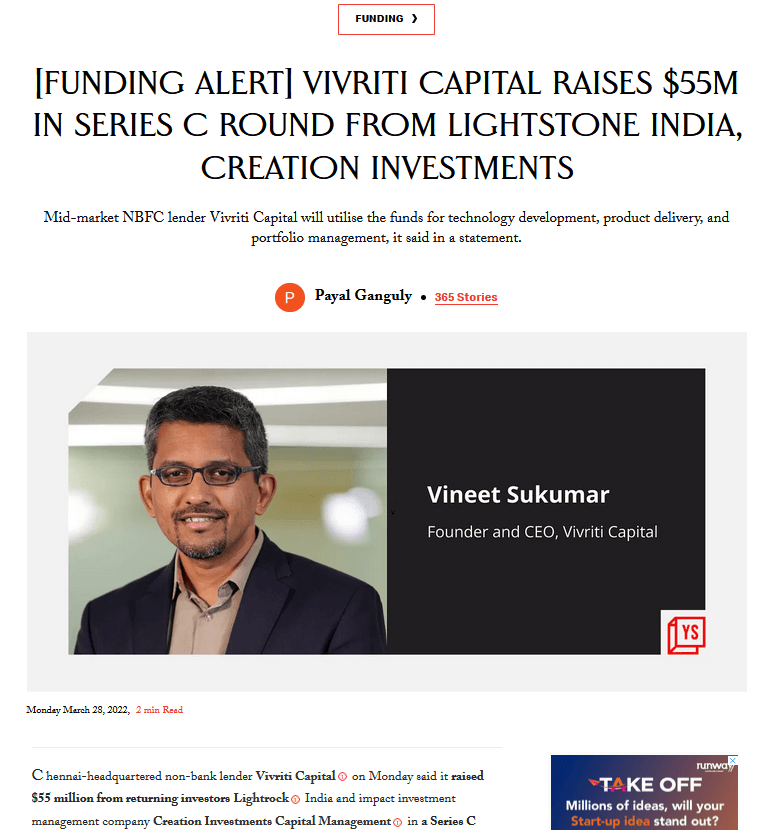

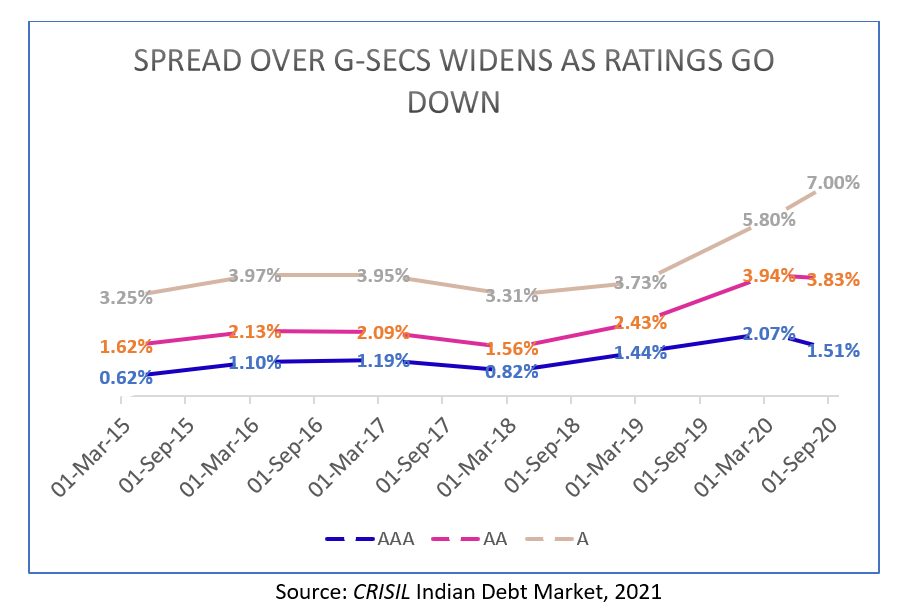

“VIRAF aims to deepen and develop India’s ABS markets, by intermediating large global capital pools to last-mile financing, thereby setting a prototype for more such vehicles. Our research indicates that Indian ABS have outperformed internationally better rated ABS, which makes Indian ABS a compelling opportunity for global investors. M&G and IFC’s participation serves as a validation of the huge and untapped potential of Indian ABS as an asset class, stability of the regulatory environment, and India’s positive macro-outlook,” said Vineet Sukumar, Founder and MD, VAM.

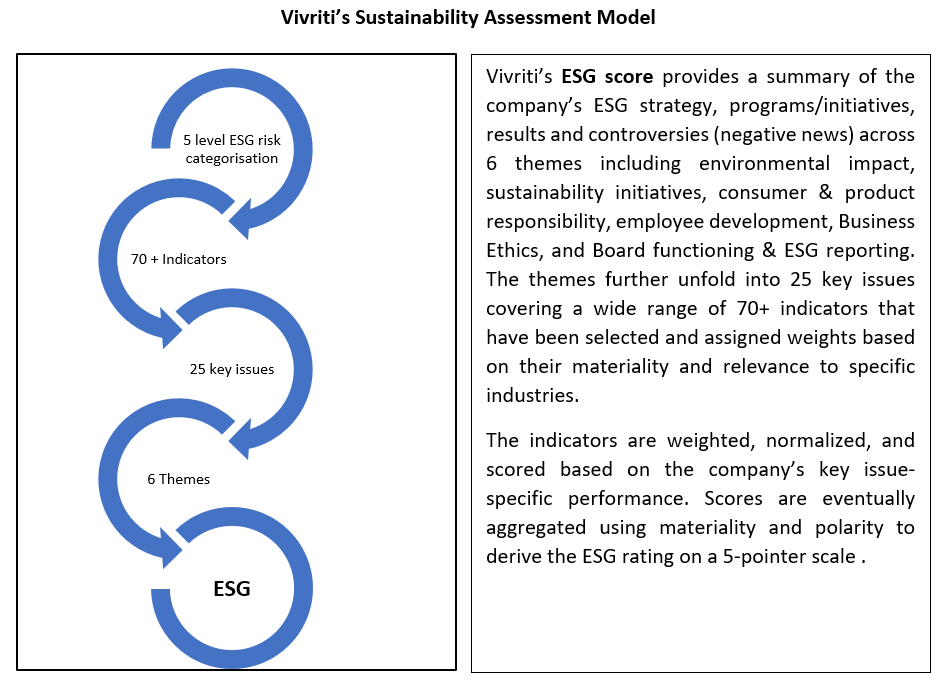

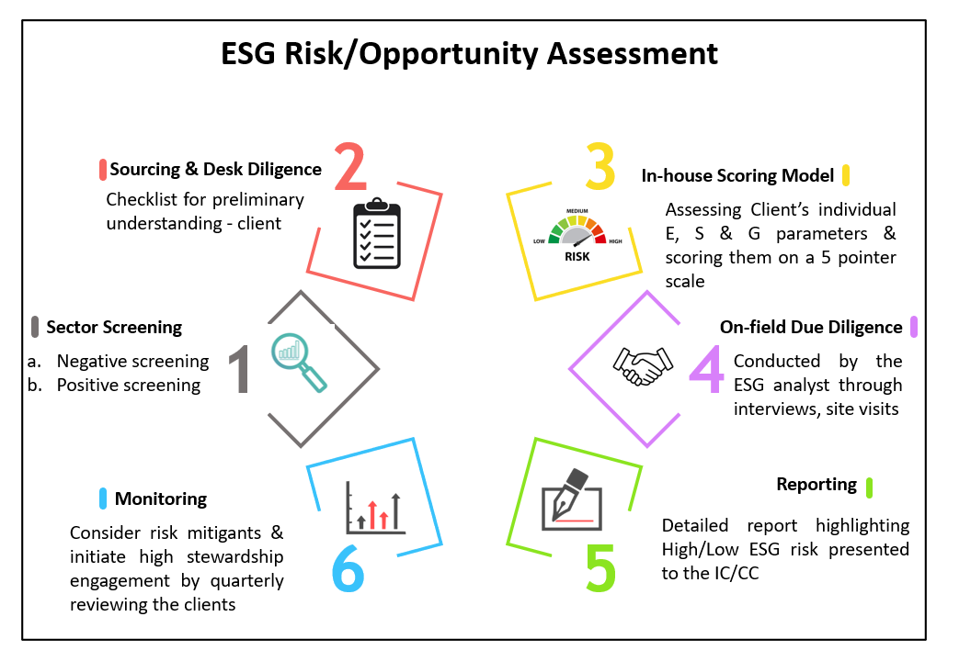

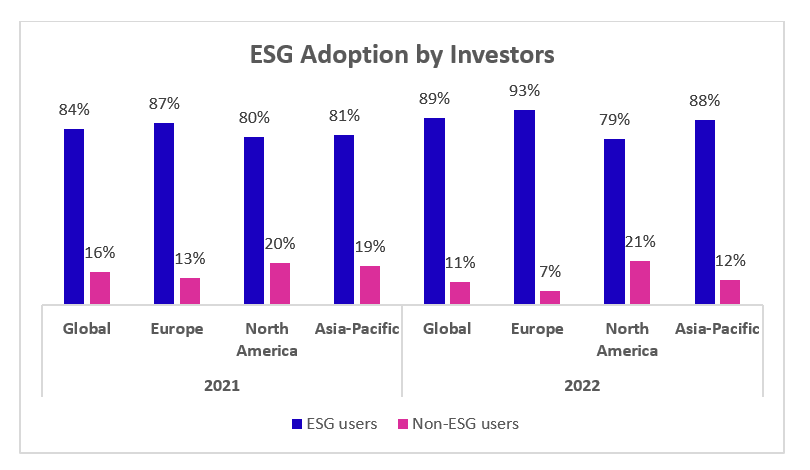

“Small and mid-sized NBFCs are at the forefront of India’s financial inclusion initiatives, allowing entrepreneurs to start and grow businesses, and low-income families to manage their finances. M&G Catalyst is a strategy which aims to deliver positive impact to society and the environment alongside financial returns, so we are particularly pleased that VIRAF is focusing on ESG assessment and engagement with IFC, helping them to become exemplary responsible and sustainable businesses,” said Matthew O’Sullivan, M&G’s Head of Origination APAC for Private Assets.

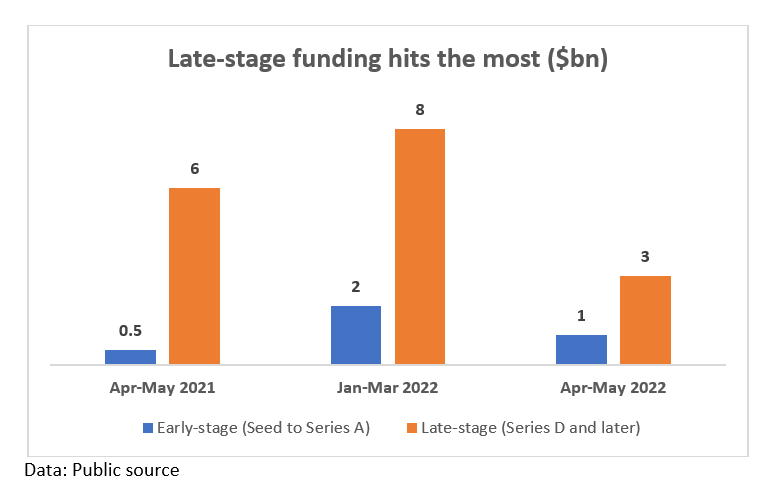

Further, the financing gap for Women-owned MSMEs is estimated at $158 billion, equivalent to about 49 percent of the total MSME finance gap in India. Addressing this challenge, the project is designed to cater to the needs of WMSEs with at least 45 percent of the Fund’s proceeds earmarked for them.

“Supporting IFC’s systematic approach, this investment will bolster India’s NBFCs and enable greater institutional funding to the sector, contributing to the financial sector’s resilience while also strengthening MSMEs post-pandemic,” said Allen Forlemu, IFC’s Regional Industry Director for Financial Institutions Group, Asia and the Pacific. “The fund will further showcase the attractiveness of securitization as a means to access capital markets, promoting similar innovative vehicles, expanding financial inclusion and fostering greater integration within the country’s capital markets.”

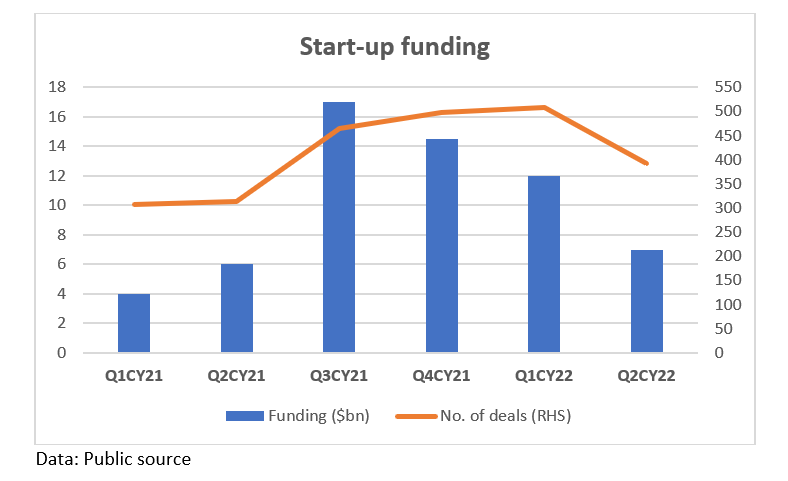

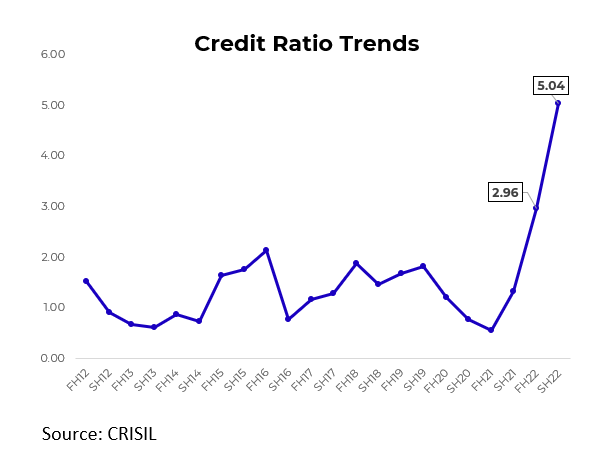

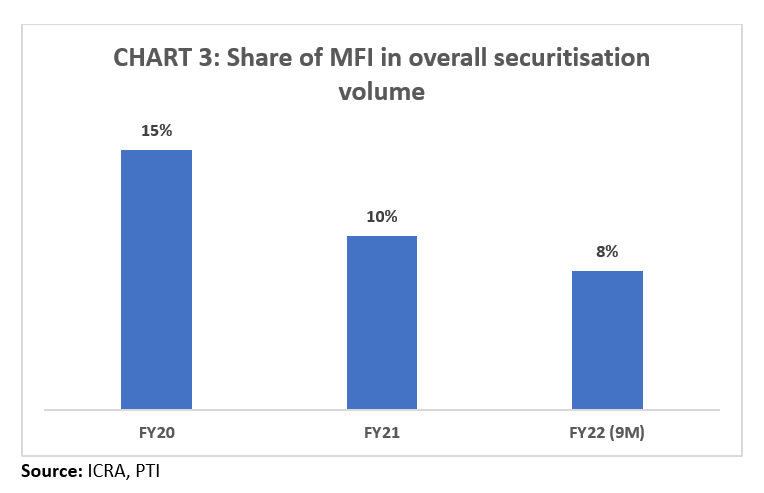

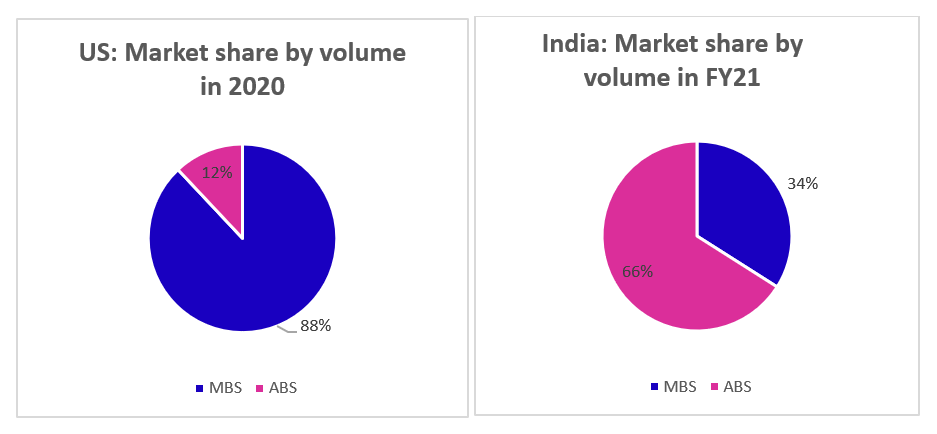

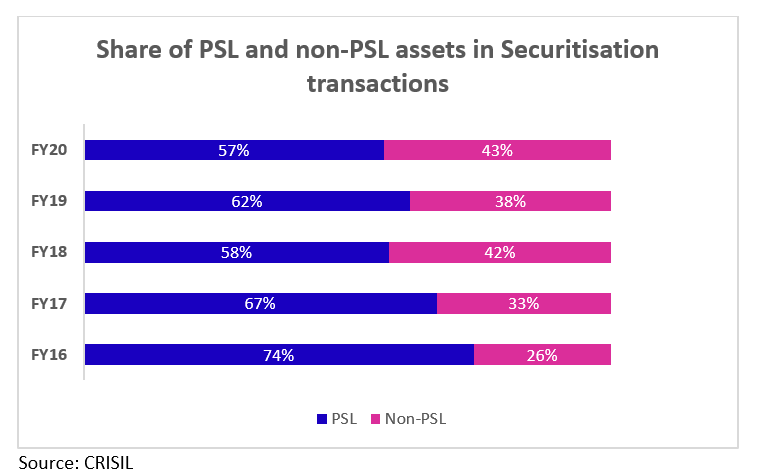

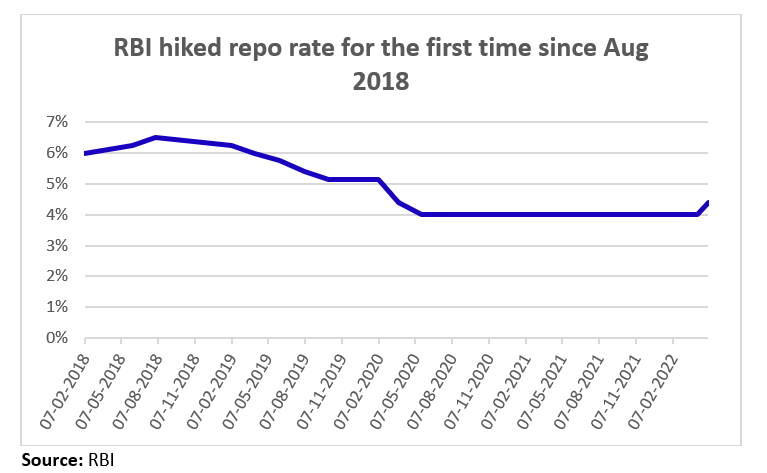

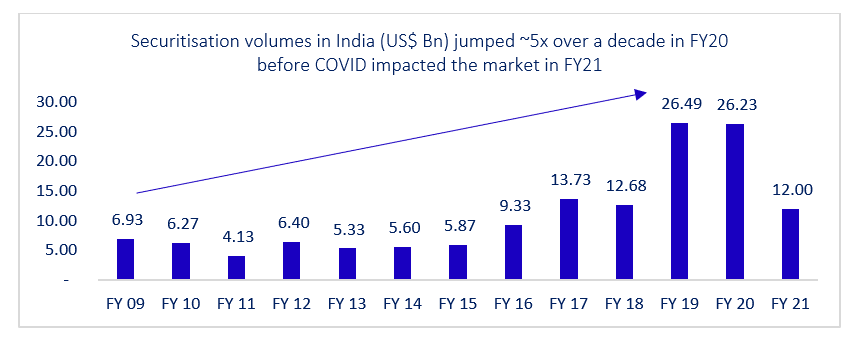

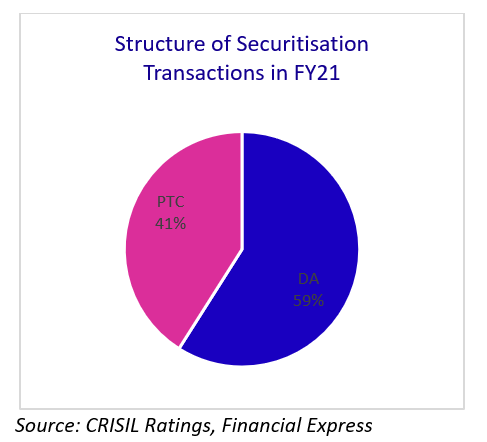

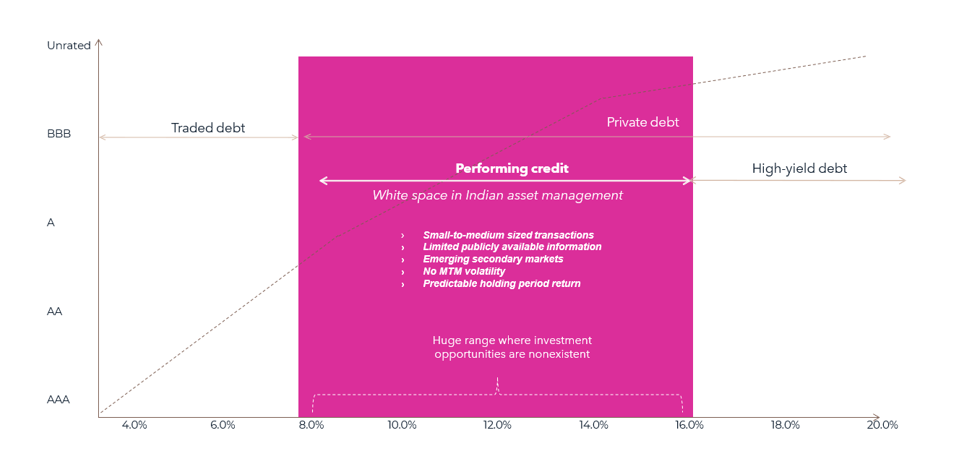

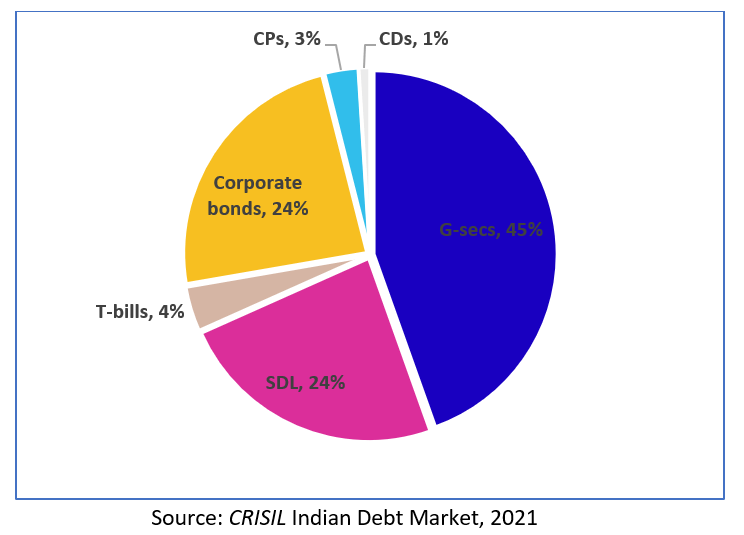

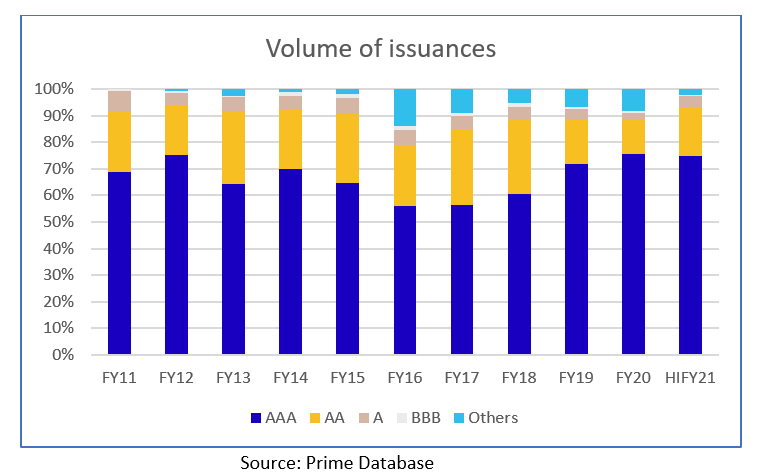

The Indian securitization market remains nascent and underdeveloped compared to other emerging economies, underscoring the need for a robust and efficient debt capital market that offers sustainable solutions to bridge the MSME finance gap. The fund supports this market’s growth, promoting greater participation from investors and originators, and channeling capital towards bolstering financial inclusion.

About VAM

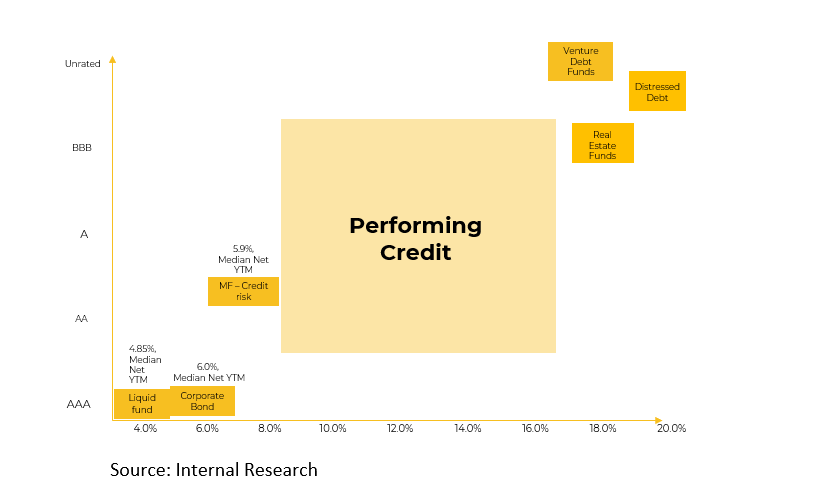

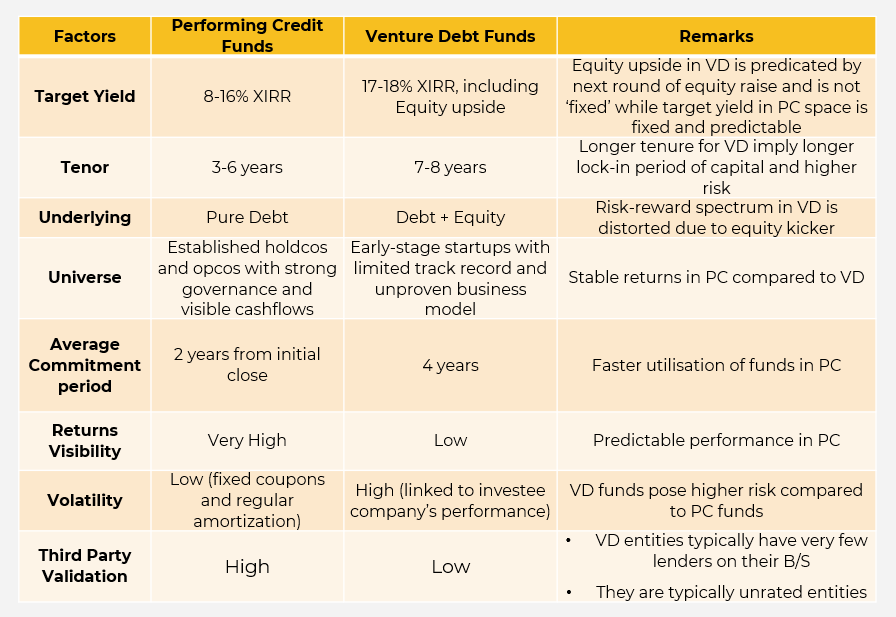

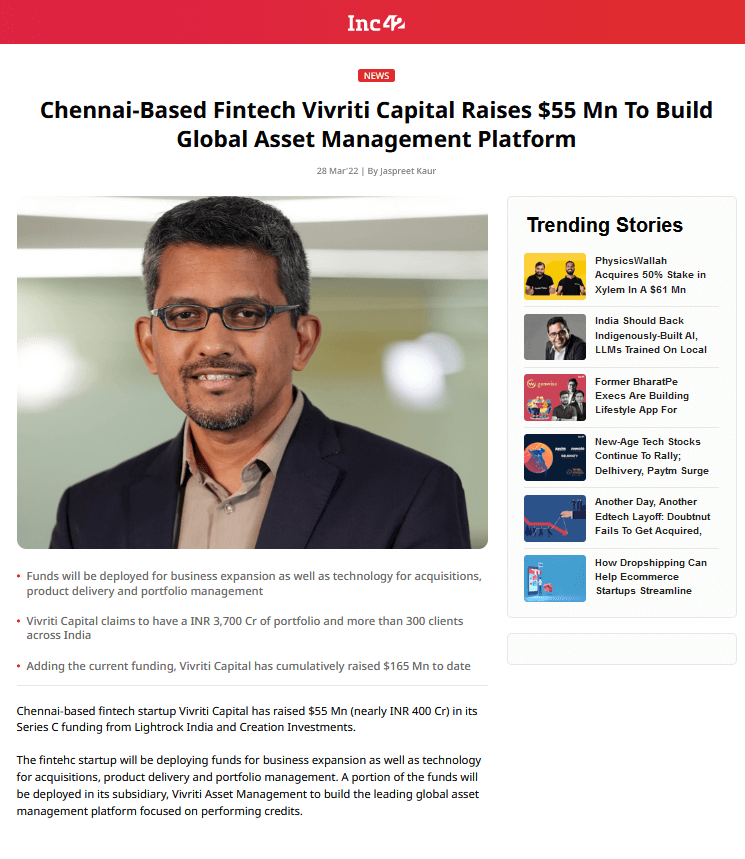

Vivriti Asset Management (VAM) is a performing-credit focused asset manager, investing in debt issued by mid-sized enterprises. With commitments of c.US$400 million across 8 funds, VAM manages sector-agnostic funds that have invested across infrastructure, energy, logistics, financials, Saas and services businesses.

Vivriti Asset Management Private Limited (IFSC branch) is registered with International Financial Services Centres Authority (IFSCA) as a Registered FME (Non-Retail) and the Investment Manager for Vivriti Fixed Income Fund – Series 3 IFSC LLP (trade name of Vivriti India Retail Assets Fund). VIRAF is a restricted scheme (non-retail) under the IFSCA (Fund Management) Regulations, 2022.

About IFC

IFC—a member of the World Bank Group—is the largest global development institution focused on the private sector in emerging markets. We work in more than 100 countries, using our capital, expertise, and influence to create markets and opportunities in developing countries. In fiscal year 2022, IFC committed a record $32.8 billion to private companies and financial institutions in developing countries, leveraging the power of the private sector to end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity as economies grapple with the impacts of global compounding crises. For more information, visit www.ifc.org

About M&G Investments

M&G’s Catalyst investment strategy sits within the Private & Alternative Assets division at M&G. With over two decades of experience in private asset investment, M&G already manages over £77 billion in private credit, private equity and real estate on behalf of Prudential policyholders and external clients. Drawing on this expertise and track record in private assets, Catalyst is a global, flexible strategy investing in private companies with innovative solutions to some of the world’s biggest environmental and social challenges. M&G Investments is part of M&G plc, a London Stock Exchange-listed savings and investment business with over €400 billion of assets under management (as at 31 December 2022). M&G plc has customers in the UK, Europe, the Americas and Asia, including individual savers and investors, life insurance policy holders and pension scheme members.

For more information, visit www.vivritiamc.com

![Funding and acquisitions in Indian startups this week [06-11 Mar]](http://dev.vivritiamc.co.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Funding-image.jpg)